Domestic Credit to the Private Sector by Banks within East Africa Economic Block

Abstract

The study analyses determinants of domestic credit to the private sector by commercial banks within the East Africa economic block. The determinants are split into two; bank-specific and non-bank specific. Error Correction Model is applied to data from four out of the six member states for the period 2013 to 2016. Based on the vector error correction model, there is a statistically significant relationship between domestic credit by commercial banks to the private sector and bank liquidity, deposit rate offered by banks, business regulation, government enterprise & investment and consumer price index.

Keywords: domestic credit, the private sector, commercial bank, economic block

Introduction

Banks primarily engage in lending where they strive to earn a return on credit facilities issued with the borrower accessing capital for investment or consumption purposes. Banks play an important role in the evolution of gross domestic product in any economy (Duican Moisescu & Pop, 2015). Investment as a component of GDP is hit hardest than consumption although it recovers quickly in times of credit shocks (Duchi & Elbourne, 2016). The private sector contributes a lot to the economic growth but for continuous investment must have access to finances. The source of funding could either be equity, debt or a mixture of the two. One major source of credit facilities is the banking industry as such their capacity and capability to offer these services is critical.

Private investment in emerging economies such as those in Africa, depend to a larger extent on external funding to expand their operations. One approach to financing is by seeking medium to long-term credit facilities from banking institutions. However, the level of borrowing has an impact on the firm if not checked. The level of debt has a significant negative effect on an enterprise investment whereas its maturity is insignificantly related to investment rate. The negative relationship between leverage and firm investment stands for private firms with long-term credit facilities from banks (Phan, 2018). But the negative effects are not a deterrent to firms seeking loan facilities which are well structured. Soundness of the banking industry is critical and from time to time Central banks tend to vary the required reserve ratio as a monetary policy tool. Changes in reserve requirements impact on the ability of banks to lend or how they grow their loan portfolio (Fungáčová, Nuutilainen, & Weill, 2016).

Lending capacity for banks improves with an increase in core capital. Banks with huge capital bases are viewed as being more stable and liquid. Liquidity status has a positive but perverse impact on bank-lending-growth, thus need to check on heterogeneous banks’ characteristics and behaviors when formulating new regulatory policies (Ben Naceur, Marton, & Roulet, 2018). The issue of bank regulatory policies is more important in the East Africa Community. Kenya in 2016, introduced a price ceiling on interest rate levied on loans advanced as well as deposit rate floor on savings accounts. The introduction of such regulation by a member state in a free economy might have effects on bank operations in the long-term. Active government borrowing from domestic financial institutions equally impacts lending by banks. Crowding out is bound to happen if a government borrows heavily in the domestic market, as banks find such borrowing to be risk-free. Further, an upsurge in asset purchases by central bank reduces the banks’ balance sheet capability to provide credit facilities to the private sector (Salachas, Laopodis, & Kouretas, 2017).

Countries within the East Africa Community (EAC) joined to form one common market and have legislation regulating the economic environment. The common market has offered private investors a vast market with numerous investment opportunities. The increased opportunities have to be financed and banks in the region play a critical role. To this end, the paper limits itself on four out of six countries that form the East Africa common market. The study focuses on determinants of domestic credit by banks to the private sector in the region. The factors have been split into two; those are specific to banks and non-bank specific.

The following sections of the paper are organized as follows. Section 2; review of the relevant literature. Section 3; the research methodology, Section 4; empirical results and, Section 5; a summary and conclusion of the paper.

Literature Review

Bank lending significantly depends on bank-specific characteristics and the macroeconomic environment; however, of bank market structure has no significant impact (Vo, 2018). The markets share and competitiveness of a bank depends on its specific characteristics. Changes in monetary policy by central or federal banks affects the pricing of loans by commercial banks and so is the deposit rate of interest. (Sanfilippo-Azofra, Torre-Olmo, Cantero-Saiz, & López-Gutiérrez, 2018) find that the loan supply by banks operating in economies with less developed financial systems is not influenced by monetary policy. The growth of loans is more sensitive to changes in the size of the bank and capitalization (Matousek & Solomon, 2018). The significance of economic policy uncertainty on lending by banks relies critically on national prudential regulations. Economic policy uncertainty significantly hampers the growth of bank credit, with the negative impact being greater in larger and riskier banks but weaker in more liquid banks and more diversified banks (Hu & Gong, 2018).

Some studies on domestic credit consider broader aspects that are either internal, external to a country or a combination of both. Loose monetary policy, differences between domestic and global lending rates and real trade openness positively contribute to domestic credit expansion levels, whereas external balance and perceptions of global tail risk negatively impact (Gozgor, 2014). Gozgor (2018) finds that income and the money supply have a desirable effect on domestic credit while current account balance and the interest rate differentials have a negative impact. Domestic factors such as monetary policy play an important role in aiding credit growth as compared to external factors. Additionally, higher exchange rate flexibility facilitates financial stability by minimizing the role of external forces influencing domestic credit dynamics (Elekdag & Han, 2015).

Banerjee and Mio (2018) state how banks always vary the composition of both assets and liabilities to the meet the liquidity requirement, furthermore, there is no evidence that banks shrink their balance sheets or reduce lending as a result of tight liquidity regulations. Imran and Nishat (2013) argue that foreign liabilities, domestic deposits, economic growth, exchange rate, and the monetary policy significantly dictate bank credit to the private sector in the long run. Moreover, inflation and money market rate have no impact on the private credit. However, the financial status and liquidity of the banks play a key role in the determination of credit facility. The deposit rate a bank offers to its customers determines domestic credit. A higher deposit rate translates to more compensation to the providers of funds the bank uses for onwards lending; this essentially reduces available loanable funds. Uchino (2014) examined the deposit rate setting behavior of regional banks in Japan.

Mushtaq and Siddiqui (2017) analyzed the effect of interest rates on bank deposits in 23 non-Islamic and 23 Islamic countries. The study concludes that interest rate has no impact on bank deposits both in short run and long run in Islamic economies. However, interest rates have a positive and significant impact on bank deposits in non-Islamic economies. Using a sample of 20 countries with dual banking systems, Meslier, Risfandy, and Tarazi (2017) demonstrate significant differences in the determinants of Islamic and conventional banks’ pricing strategies. Conventional banks with bigger market share set lower deposit rates whereas market power is not significant for Islamic banks. Moreover, conventional banks offer higher deposit rates and even higher when their market power is lower in predominantly Muslim markets. Depositors are not being significantly over-compensated in euro area countries since the financial crisis, this differs with what is often perceived (Pinter & Boissel, 2016).

Policy aimed at minimizing inflation bias is desirable as it helps achieve low stable inflation and sustainable real economic growth (Hayat, Balli, & Rehman, 2018). Cogoljević, Gavrilović, Roganović, and Matić (2018) analyzed the interaction between inflation and consumer price index. Economies with higher levels of fiscal transparency experience both lower inflation rates and inflation volatility; also, fiscal transparency has a stronger effect on inflation (Caldas & Leitão, 2018). The role played by a government in enhancing private investment can be assessed through two angles, government size, and governance quality. Changes in public governance quality are important factors that improve the impact of government size on private investment (Su, Mai, & Bui, 2017).

Business regulation has a significant positive influence on economic growth, the effect is more pronounced in countries regulatory quality is worse and in middle-income countries (Silberberger & Königer, 2016). Haidar (2012) investigated the relationship between business regulatory reforms and economic growth in 172 countries and concludes that each business regulatory reform is associated with a 0.15% increase in GDP growth rate. Korutaro and Biekpe (2013) studied the impact of business regulations on investment noting that fewer administrative procedures have a positive and significant effect on investment in any given economy. Noman, Gee, and Isa (2018) developed a framework to determine bank regulation geared at enhancing financial stability. Financial regulation through capital yield tax rectifies negative effects on growth, furthermore, financial inefficiency has a negative impact on growth (Rivas Aceves & Amato, 2017). Messaoud and Teheni (2014) analyzed the relationship between business regulations and economic growth in 162 countries and find that regulation scores and control variables are not important for growth induction in Africa.

In conclusion, few focus entirely on domestic credit to the private sector by commercial banks for small emerging economies. Findings on the determinants of domestic credit have had varying conclusions in some instances, this allows for further studies to be performed on the subject. Regional economic blocks are gaining traction in today’s competitive and dynamic business environment. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study dedicated to determining factors that are significant to the availability of credit to private domestic investors or consumers within emerging East African economic block.

Research Design and Sample Selection

Data and Test Variable

Domestic credit to the private sector by banks is used as a dependent variable. The study takes into account factors specific and non-specific to banking institutions. The data for the period 2003 to 2016 was used to analyze determinants of domestic credit to the private sector by commercial banks within the East Africa economic block. Data used was obtained from two sources namely the World Bank and Fraser Foundation database. The initial sample comprised of data from five out of six member countries. However, Southern Sudan was dropped since it joined the Community in the last year of the study period whereas Burundi incomplete data. Therefore, data used is on Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and Rwanda in order of their economic strength. The selected variables were log-transformed to satisfy the requirements of data analysis technique.

Bank specific variables are; liquidity levels (LNBL) and deposit interest rate (LNDR) whereas non-bank specific factors are; regulation of the business environment (LNBR), government enterprise & investment (LNGEI) and consumer price index (LNI). The dependent variable is domestic credit to the private sector by banks (LNDCB), below is a brief outline of how the variables were used in the study.

Deposit interest rate what is paid by commercial banks for time, demand or savings deposits. Domestic credit to the private sector by banks refers to credit facilities extended to the private sector which establishes a claim for repayment. Bank liquidity is the ratio of local currency held and deposits with the monetary authorities to claims on other public or private institutions. Business regulation entails costs attributable to; administrative requirements, bureaucracy costs, starting a business, licensing restrictions and cost of tax compliance. Government enterprise and investment is the level to which countries utilize private investment and enterprises rather than government investment and firms to direct available resources. The consumer price index is the annual percentage change in the cost to the average consumer of acquiring a basket of goods and services.

3.2 Descriptive Statistics

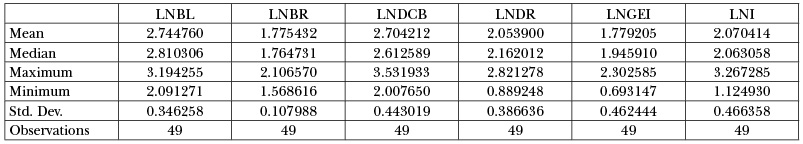

Table 1 shows the log-transformed variables used in the study indicating their mean, median both minimum and maximum values. Note that the expected sample is 56, that is, time series observations of 14 years for each of the four countries. However, due to the log transformation of the variables, some data (negative observations) was lost and the net effect is a reduced sample of 49.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Variable

3.3 Methodology

A unit root is a characteristic of some stochastic processes that would be problematic in drawing statistical inference relating to time series models. It can cause any analysis to have serious econometric shortcomings such as errant behavior and spurious regressions. In analytical techniques such as error correction modeling, the process is performed under the assumption that data is stationary. Such an assumption is made when analyzing time series with classical methods like ordinary least squares. It is assumed that the variances and means of the series are constants independent of time, that is, the processes are stationary. When there is a non-stationary time series or unit root variables violating this assumption, any hypothesis test results are unreliable. Unit root tests have to be performed using techniques such as Dickey-Fuller and KPSS test. Augmented Dickey-Fuller Test (ADF) addresses the challenges of serial correlation in time series data. ADF is based on first order auto-regression (AR) process as shown below;

γt = ∅γt–1 + ∈t t = 1,2…..T

The above AR (1) Dickey-Fuller test can be extended to ADF, AR (p)

γt = ∅ 1 γt–1+ ∅ 2 γt–2 + ∅ p γt–p

Where a unit root is given by:

∅(L) = 1 – ∅1L – ∅ 2L2 – ∅ PLP

Based on Dickey and Fuller test, the null hypothesis;

H0 : δ = 0 implies non-stationarity or presence of a unit root. The alternative hypothesis; H1 : δ ≠ 0 means the absence of a unit root (stationarity) which is the desirable state. Stationarity state for all the variables was obtained after first differencing.

Table 2 shows the ADF unit root test for all the variables

Table 2. Unit Root Test for the Variables

|

Statistic |

Probability |

|

|

LNDCB |

-7.1103 |

0.0000 |

|

LNBL |

-9.8346 |

0.0000 |

|

LNBR |

-6.2347 |

0.0000 |

|

LNDR |

-7.0505 |

0.0000 |

|

LNGEI |

-8.3442 |

0.0000 |

|

LNI |

-10.1781 |

0.0000 |

Table 2 above shows that all the variables become stationarity after the first differencing. Note that where the probability is more than 5 percent, then the variable has a unit root. There are studies that have used similar approaches or attempted to improve on the same such as Tu (2017; Zhang and Chan (2018).

Estimating the right lag length of an autoregressive process for a time series is an important econometric step. A number of information criteria have been developed over time with the commonly used approach being Akaike Information Criterion (Angelini, 2018). Liew (2004) finds that Akaike information criterion (AIC) and final prediction error (FPE) is superior to the other criteria in studies with small sample size, that is, 60 observations and below. However, there are other information criteria such as Schwarz (SC), Hannan-Quinn (HQ) and Sequential modified (LR) statistic test. In this study, all five criteria gave a one lag selection.

Where a linear combination of two variables has a lower order of integration, the two sets of variables are cointegrated. When a set of I (1) variables are modeled with linear combinations which are I (0), then there is cointegration. The integration order indicates that a single set of differences can transform the non-stationary to stationarity variables. One approach to testing cointegration is Johansen test an improvement on Engle-Granger test where more than one cointegrating relationship is possible. Johansen test of cointegration is addressed problems associated with selecting a dependent variable or where errors are carried from step to next.

If: γt = (γ1t, γ2t … … … γnt)’ denotes (n × 1) vector of I (1) time series

Then; γt is cointegrated when: β′ γt = β1γ1 + β2γ2 + … + βnγnt∼I(0)

Normalization uniquely identifies β as; β = (1, – β2, – β3 … βn)’

Thus, the cointegrating relationship can be expressed as:

γ1t = β2γ2 + β3γ3 + … + βnγn + ut∼I(0)

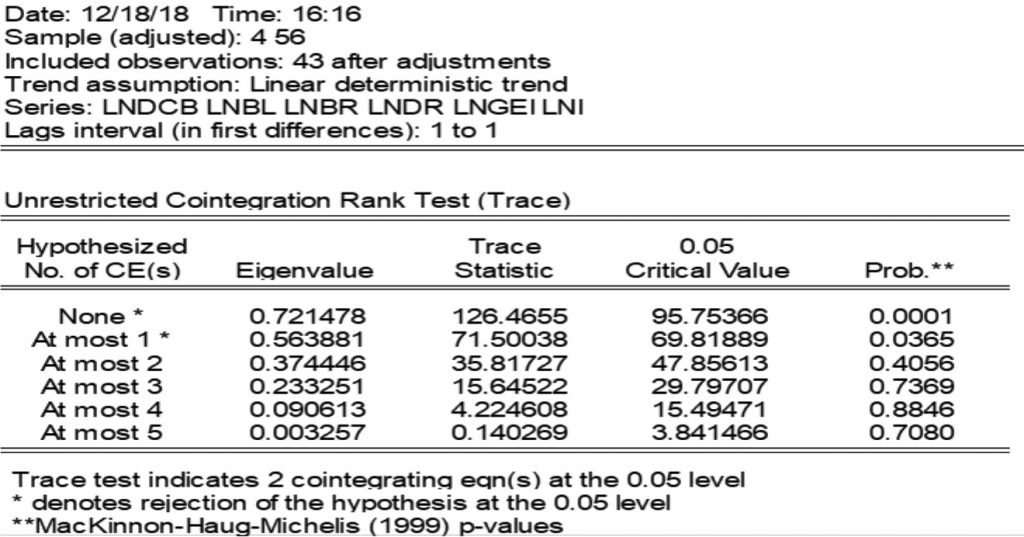

Table 3 Co-integration Test between variable series

Table 3 shows the results of the long run relationship between the dependent and predictor variables. The null hypothesis is that there is no cointegration between the series. However, the alternative hypothesis assumes the presence of co-integration between the series. From the table, the null hypothesis is rejected at 5 percent level for the first two instances, implying a long run relationship between the variables. However, we fail to reject the null hypothesis in the rest of the cases. The normalization equation can be inspected to check on the nature of the relation between the variable series.

Vector error correction model (VECM) is developed to examine both the short and long term dynamics of the time series. The conventional error correction model for the co-integrated series is given as:

Where;

- Z is the error correction term (ECT) and OLS residuals for the long-run co-integration

- φ the coefficient of ECT, is the speed of adjustment as it measures the rate at which Y returns to equilibrium after a change in X

4 Empirical Findings

Shown below is the normalization equation between domestic credit to the private sector by banks as dependent and independent variables.

Note that in the long run, the sign of the co-integrating coefficients is reversed. In the long run, bank-to-asset liquidity, business regulation, and government enterprise and investment have a positive impact on whereas bank deposit rate and consumer price index have a negative impact on domestic credit to the private sector by commercial banks on average ceteris paribus. The five coefficients are statistically significant at 5 % level.

In the long run, an increase in bank liquidity-to-assets, government enterprise & investment and improved business regulation are associated with an upsurge in domestic credit to the private sector by banks and vice versa. Lending grows when bank capital increases whereas the reduction effect of funding liquidity on bank lending vary with capital (Dahir, Mahat, Razak, & Bany-Ariffin, 2018). Kalyvas and Mamatzakis (2014) argue how desirable regulation of the business environment has a positive impact on bank regulation. Where the state has privatized its enterprise and held a minority share, the firm was found to be a better investment and efficient (O’Toole, Morgenroth, & Ha, 2016).

Similarly, a decrease in both deposit rate and consumer price index results in an increase in domestic credit provided by banks to the private sector and vice versa equally in the long run. In the real economy, production is subject to variation due to the interplay of economic factors. This tends to influence the level of inflation of that particular economy as captured by the consumer price index. Uchino (2014), equally analyzed Japanese deposit markets by focusing on deposit rate aimed at ascertaining the level of geographic segregation. Output fluctuations majorly affect bank lending capacity (Pool, de Haan, & Jacobs, 2015).

Based on the co-integration coefficient and standard error, the t-statistics are: -5.70, -4.36, 5.10, -4.75 and 1.12 for the predictor variables. Thus, the null hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected in favor of the alternative of a cointegrating relationship in the model.

Estimated VECM with LNDCB as the target variable is given as:

ΔLNDCBt = 0.6369ectt–1

+ 0.2219 Δlnblt–1 – 0.1312Δlnbrt–1

– 0.0284Δlndrt–1 – 0.948Δlngeit–1

+ 0.239Δlnit–1 + 0.0090

Thus, the long-run model co-integrating equation is:

ECTt–1 = 1.0000lndcbt–1 – 0.1681lnblt–1 – 0.5547lnbrt–1

– 0.1711lndrt–1 – 0.1301lngeit–1 – 0.0269lnit–1 + 0.8876

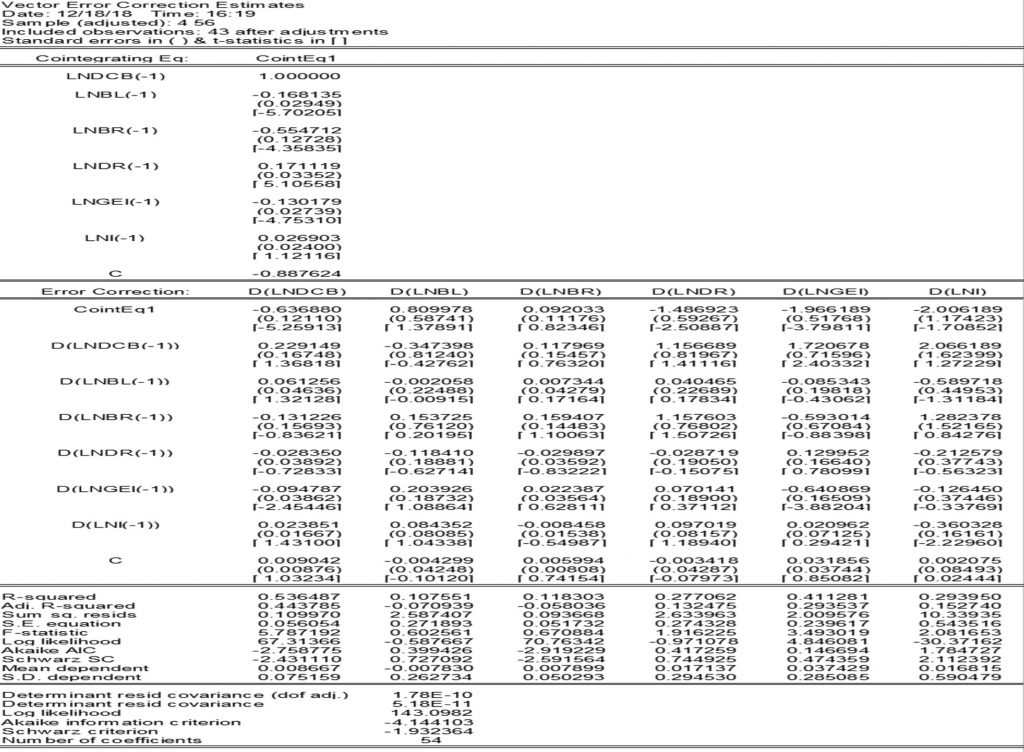

Table 4. Error Correction Estimates

Table 4 above shows the model specification in the natural log and as such the interpretation is in terms of elasticity bearing in mind reversal of the signs. The first part of the table shows the cointegrating equation and the long-run relationship between the variables. For example, a one percent change in bank liquidity-to-asset ratio will result in a 0.168 percent increase in domestic credit to the private sector by banks. Similarly, a one percent change in bank deposit rate leads to 0.171 percentage decrease in domestic credit and so on. The second part of the table on error correction shows an error correction term and short term adjustment coefficients. For example, the previous period deviation from long-run equilibrium is corrected in the current period at an adjustment speed of 63.688%. A 1% change in bank deposit is associated with a 0.0284% decrease in domestic credit to the private sector by banks; whereas a similar change in consumer price index is associated with a 0.0239% in the dependent variable.

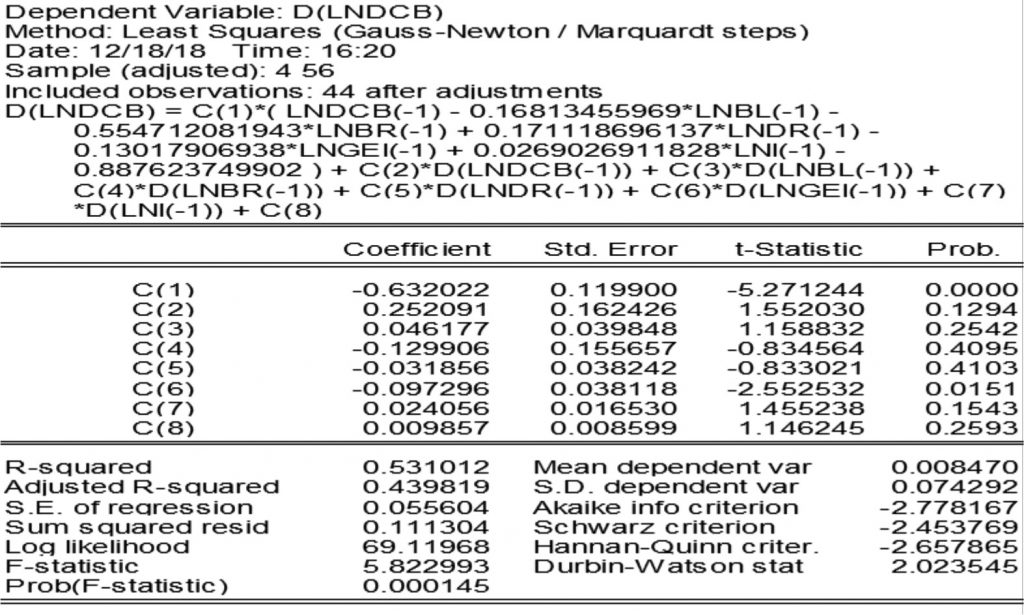

To test whether the ECM is statistically significant and draw a conclusion on both the short-run and long-run causality, p values are analyzed. Table 5 below shows the estimated error correction equation with coefficients and associated p values.

Table 5. P-value statistics

Table 5 shows that the phi [φ] is -0.6320 and statistically significant at 5 percent confidence interval. The negative sign implies that any deviation from the equilibrium point will be corrected by a movement in the opposite direction in the long run. Thus, about 63.20 percent of deviations from long-run equilibrium is corrected each period (in the opposite direction). Therefore, it can be concluded that there is a long run relationship between domestic credit to the private sector by banks and bank liquidity-to-assets, business regulation, bank deposit rate, government enterprise & investment and consumer price index.

5 Conclusion

Member states of the East Africa economic block are small emerging markets if viewed as separate units but a huge economy when analyzed collectively. Financial institutions such as banks are major determinants of the extent to which domestic credit is readily available to the private sector for investment purposes. Each member state pursues its own fiscal and monetary policies although there are negotiations for a monetary union. In this study, 14 years of each country data (2003-2016) was used to determine factors that dictate the availability of domestic credit to the private sector by banks within the economic block.

Domestic credit to the private sector by banks the dependent variable, whereas bank liquidity-to assets ratio, business environment, bank deposit rate, government enterprise & Investment, and consumer price index were the explanatory variables. According to the results of the vector error correction model, improvements in bank liquidity-to-assets, government enterprise & investment and business regulation result in an increase in domestic credit to the private sector by banks. Additionally, low or falling bank deposit rates and consumer price index equally lead to a rise in domestic credit to the private and vice versa.

This study contributes to the literature by providing new empirical evidence on the determinants of domestic credit to the private sector in emerging economic blocks by focusing only on commercial banks. The determinants were split bank and non-bank specific. Future related studies can focus on a different explanatory variable that may influence the provision of domestic credit by financial institutions to the private sector. The scope of the paper was limited to commercial banks as providers of domestic credit for private investment.

Authors’ Contribution: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing-original draft preparation, E.M.; Writing-review, editing, Supervision and project administration, Z.Z.

Funding: The study received no external funding

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest

Reference

1. Angelini, G. (2018). Bootstrap lag selection in DSGE models with expectations correction. Econometrics and Statistics, 0, 1–11.

2. Banerjee, R. N., & Mio, H. (2018). The impact of liquidity regulation on banks. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 35, 30–44.

3. Ben Naceur, S., Marton, K., & Roulet, C. (2018). Basel III and bank-lending: Evidence from the United States and Europe. Journal of Financial Stability, 39, 1–27.

4. Caldas, G., & Leitão, L. (2018). Effects of fiscal transparency on inflation and inflation expectations : Empirical

evidence from developed and devel-

oping countries. Quarterly Review of

Economics and Finance, 70, 26–37.

5. Cogoljević, D., Gavrilović, M., Roganović, M., & Matić, I. (2018). Analyzing of consumer price index influence on inflation by multiple linear regression. Physica A, 505, 941–944.

6. Dahir, A. M., Mahat, F., Razak, N. H. A., & Bany-Ariffin, A. N. (2018). Capital, funding liquidity, and bank lending in emerging economies: An application of the LSDVC approach. Borsa Istanbul Review.

7. Duchi, F., & Elbourne, A. (2016). Credit supply shocks in the Netherlands. Journal of Macroeconomics, 50, 51–71.

8. Duican (Moisescu), E. R., & Pop, A. (2015). The Implications of Credit Activity on Economic Growth in Romania. Procedia Economics and Finance, 30(15), 195–201.

9. Elekdag, S., & Han, F. (2015). What drives credit growth in emerging Asia? Journal of Asian Economics, 38, 1–13.

10. Fungáčová, Z., Nuutilainen, R., & Weill, L. (2016). Reserve requirements and the bank lending channel in China. Journal of Macroeconomics, 50(March), 37–50.

11. Gozgor, G. (2014). Determinants of domestic credit levels in emerging markets: The role of external factors. Emerging Markets Review, 18, 1–18.

12. Gozgor, G. (2018). Determinants of the domestic credits in developing economies: The role of political risks. Research in International Business and Finance, 46(April), 430–443.

13. Haidar, J. I. (2012). The impact of business regulatory reforms on economic growth. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 26(3), 285–307.

14. Hayat, Z., Balli, F., & Rehman, M. (2018). Does inflation bias stabilize real growth? Evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Policy Modeling, 40(6), 1083–1103.

15. Hu, S., & Gong, D. (2018). Economic policy uncertainty, prudential regulation, and bank lending. Finance Research Letters, (August), 1–6.

16. Imran, K., & Nishat, M. (2013). Determinants of bank credit in Pakistan: A supply-side approach. Economic Modelling, 35, 384–390.

17. Kalyvas, A. N., & Mamatzakis, E. (2014). Does business regulation matter for banks in the European Union? Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions, and Money, 32(1), 278–324.

18. Korutaro, B., & Biekpe, N. (2013). Effect of business regulation on investment in emerging market economies. Review of Development Finance, 3(1), 41–50.

19. Liew, V. (2004). Which Lag Length Selection Criteria Should We Employ ? Economics Bulletin, 3(33), 1–9.

20. Matousek, R., & Solomon, H. (2018). Bank lending channel and monetary policy in Nigeria. Research in International Business and Finance, 45(October 2016), 467–474.

21. Meslier, C., Risfandy, T., & Tarazi, A. (2017). Dual market competition and deposit rate setting in Islamic and conventional banks. Economic Modelling, 63(November 2016), 318–333.

22. Messaoud, B., & Teheni, Z. E. G. (2014). Business regulations and economic growth: What can be explained? International Strategic Management Review, 2(2), 69–78.

23. Mushtaq, S., & Siddiqui, D. A. (2017). Effect of the interest rate on bank deposits : Evidence from Islamic and non-Islamic economies. Future Business Journal, 3(1), 1–8.

24. Noman, A. H. M., Gee, C. S., & Isa, C. R. (2018). Does bank regulation matter on the relationship between competition and financial stability? Evidence from Southeast Asian countries. Pacific Basin Finance Journal, 48(December 2017), 144–161.

25. O’Toole, C. M., Morgenroth, E. L. W., & Ha, T. T. (2016). Investment efficiency, state-owned enterprises, and privatization: Evidence from Viet Nam in Transition. Journal of Corporate Finance, 37, 93–108.

26. Phan, Q. T. (2018). Corporate debt and investment with financial constraints: Vietnamese listed firms. Research in International Business and Finance, 46 (December 2017), 268–280.

27. Pinter, J., & Boissel, C. (2016). The Eurozone deposit rates’ puzzle : Choosing the right benchmark. Economics Letters, 148, 33–36.

28. Pool, S., de Haan, L., & Jacobs, J. P. A. M. (2015). Loan loss provisioning, bank credit, and the real economy. Journal of Macroeconomics, 45, 124–136.

29. Rivas Aceves, S., & Amato, C. (2017). Government financial regulation and growth. Investigacion Economica, 76(299), 51–86.

30. Salachas, E. N., Laopodis, N. T., & Kouretas, G. P. (2017). The bank-lending channel and monetary policy during the pre- and post-2007 crisis. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions, and Money, 47, 176–187.

31. Sanfilippo-Azofra, S., Torre-Olmo, B., Cantero-Saiz, M., & López-Gutiérrez, C. (2018). Financial development and the bank lending channel in developing countries. Journal of Macroeconomics, 55(April 2017), 215–234.

32. Silberberger, M., & Königer, J. (2016). Regulation, trade and economic growth. Economic Systems, 40(2), 308–322.

33. Su, T. D., Mai, T., & Bui, H. (2017). Government size, public governance, and private investment : The case of Vietnamese provinces. Economic Systems, 41(4), 651–666.

34. Tu, Y. (2017). On spurious regressions with partial unit root processes. Economics Letters, 150, 142–145.

35. Uchino, T. (2014). Bank deposit interest rate pass-through and geographical segmentation in Japanese banking markets. Japan and the World Economy, 30, 37–51.

36. Vo, X. V. (2018). Bank lending behavior in emerging markets. Finance Research Letters, 27(October 2017), 129–134.

37. Zhang, R., & Chan, N. H. (2018). Portmanteau-type tests for unit-root and cointegration. Journal of Econometrics, 207(2), 307–324.

Edmund Mallinguh

School of Economics and Social Sciences,

Szent István University, Godollo, Hungary

Zeman Zoltan

Institute of Business Sciences,

Szent István University, Godollo, Hungary

@ WCTC LTD --- ISSN 2398-9491 | Established in 2009 | Economics & Working Capital